Fernando Botero

Fernando botero

Born 1933

Colombian Artist

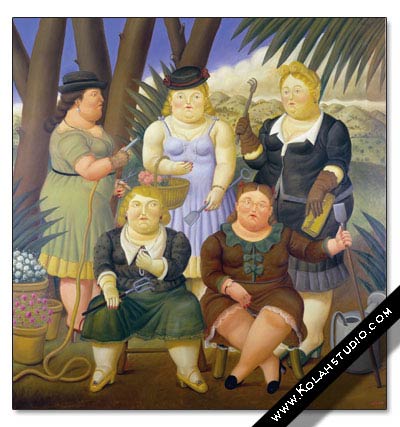

Fernando Botero, one of the most celebrated living artists in Latin America , has gained international fame and fortune capturing the whimsy of life by painting his fellow Colombians, aristocrats and workers alike, as corpulent and comical.

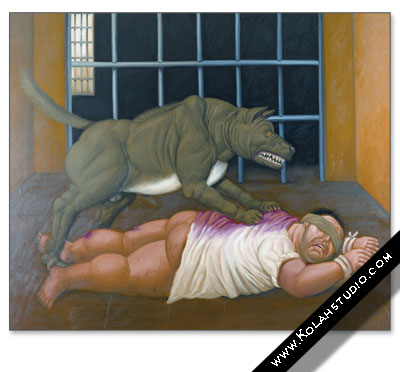

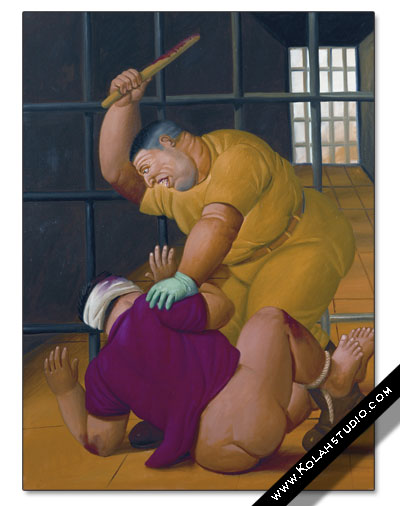

But Mr. Botero, 72, is now producing works that represent a dramatic break in substance, if not style, from his past. They are paintings that depict, in horrific detail intended to alarm and sadden, a conflict that is little understood outside Latin America : the brutal, drug-fueled guerrilla war that has been going on for 40 years in Colombia .”They are different from what I have done in the past, the kinder Colombia that I knew as a boy,” Mr. Botero, who lives in Paris and New York , said in a recentinterview. “This is a Colombia that is more violent, more real. This is the fact that we cannot ignore.”But Mr. Botero’s plan all along was to donate the works to the National Museum of Colombia here, “where they belong,” as he put it in a handwritten fax announcing the donation in February

2003.

“If they make an impression on the public, I have completed the mission of showing the absurdity of the violence,” Mr. Botero said in an interview.The exhibition, dryly titled “Botero in the National Museum of Colombia: The 2004 Donation,” officially opens on Tuesday and after two months here begins a tour of at least four other Colombian cities, including Mr. Botero’s native Medellín. Speaking as museum workers put the finishing touches on his exhibition on Thursday, Mr. Botero said he had given the museum permission to lend the collection to other museums, including institutions outside Colombia , opening the possibility that the works could travel to the United States .

In many countries plagued by conflict, years can go by before artists tackle the difficult, painful subject matter. But Colombia, where rebels first took up arms in 1964, has had a long, storied tradition of accomplished artists like Alejandro Obregón, Doris Salcedo and Débora Arango painting about the horrors of the relentless violence that has taken at least 200,000 lives.Mr. Botero, however, had conspicuously avoided addressing the conflict. Painting and sculpturing prolifically since the 1950’s, he instead recreated life in villages and alleyways, living rooms and bathrooms.

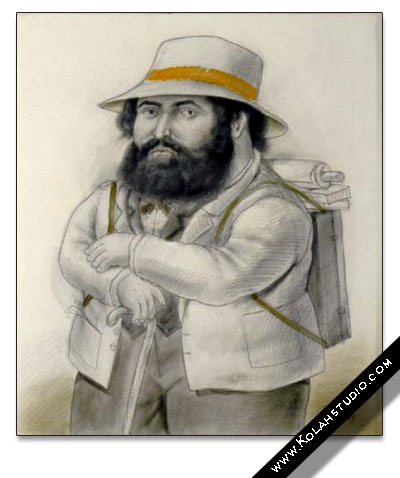

Except for his earliest works, his style since the 1950’s has varied slightly, his subjects always voluminous, as he prefers to put it.He has painted wealthy families in their Sunday best. He sketched nudes drying their hair, as well as extravagantly large oranges and bananas. He painted a s leeping president, still wearing the presidential sash, generals in elaborate uniforms and the dour mother superior of a convent.

The treasure trove of his life’s work — Mr. Botero has produced more than 2,500 works — is on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid and the Museum of Antioquía in his Medellín. His enormous bronze sculptures have sat in public spaces around the world, in 1993 even lining the median on Park Avenue.Now, almost as if he were making up for a past omission, Mr. Botero says he has put his heart and soul into creating works that touch on practically every violent aspect of the war: its kidnappings and massacres, funeral processions, car bombs and death-squad fighters.”You read about these things, this violence, and this produces an impact on you,” he explained. “As an artist you want to reflect on this reality.”

Still, Mr. Botero said that the images he has painted were not always true to life but represented his vision of what happened.In “Massacre in the Cathedral,” a 2002 oil, he tackled a representation of the errant rebel rocket attack that killed about 120 people, including more than 40 children, huddled inside a church in May 2002.

After the attack, Mr. Botero explained, he heard a s hort radio report on it while driving in France . He imagined the destruction in a cathedral in Colombia’s colonial crown jewel, Cartagena.The painting he created in one week shows pillars overturned, an elaborate altar off kilter and the rotund bodies of Colombians, all appearing to be descendants of Europeans, buried under rubble.In reality the church was a tiny, hardscrabble chapel in Bellavista, an isolated, dirt-poor village in the jungle, its occupants all Afro-Colombians.

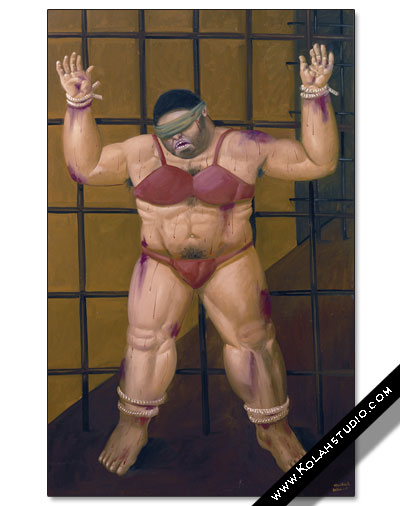

But Mr. Botero said he had accomplished his objective, to paint the senseless nature of the violence,in this case befalling the most sacred of Colombian institutions, a church.”There is no realism,” he said. “It is more a way to express the violence that has happened.”Though the paintings and sketches in the war collection maintain the bright colors and sharp texture of his other works, they are filled with raw energy and agony.”Look at the scenery, very tranquil, very placid,” Mr. Botero said standing near another painting, pointing to a church and blue sky that serve as the background to “Massacre of the Innocents.” “But then you have the drama here,” he continued, pointing to a man knifing a mother and two children in the foreground.Several of the works picture victims of kidnappings, blindfolded, naked and crying out in anguish. In “Río Cauca,” named for one of the most important rivers in Colombia , bodies float under a pale sky, vultures feeding on them. In another, Mr. Botero shows a procession of coffins, capturing the painful aftermath of a massacre.Elvira Cuervo de Jaramillo, director of the National Museum , said the paintings would probably shock Colombians used to Mr. Botero’s more placid images.”What hetransmits is immense pain when we see figures of massacres, of death, of torture,” she said. “Theydo not produce pleasure, or smiles. They are meant to move you. They chill you to your bones.”But Mr. Botero said that he had no illusions that his paintings would in some way lessen Colombia ‘s violence.He noted that ” Guernica ,” Picasso’s memorial to the Spanish town destroyed by German bombers, did not end the Spanish Civil War.”Instead, this is a hope of mine that it will be a testimonial to a terrible moment, a time of insanity in this country,” Mr. Botero said. “They are works that will hang in a museum, so people can see their history.”

Mr. Botero said that he was creating more works about the war, and had finished another two or three paintings and 10 drawings.”I have no intention of earning money exploiting Colombia ‘s drama,” he said. “These works are not for sale. They will always be donated.”Mr. Botero, who has lived outside Colombia for decades, once made frequent, lengthy pilgrimages visits back, but the threat of kidnapping forced him to limit his trips. Still, he said that he had never lost sight of his homeland, always painting Colombian village scenery.

“I’m the most Colombian of the Colombians, even though I’ve lived 47 years outside of Colombia ,” he said. “I’ve lived 13 years in New York , and I never did a painting about New York . I’ve lived in France more than 30 years, and I’ve never painted Paris .”Mr. Botero, though, said that he still dreamed of returning, setting up his studio once more and working here.”I love my country, and it hurts not to be able to see my country, as I did for so many years,” he said. “I hope that I will one day be able to live in a peaceful Colombia .”

Sources

Web Resources:

http://www.nytimes.com/ | http://www.artchieve.com